What’s in it for me as a reader

I’ve been thinking about this topic since my article on Innovation Tokens [1] in 2016. In past articles I often used the term Small Experiments. I connect a lot of semantics to that term which is all about enabling innovation in larger organisations which might otherwise struggle with Innovator’s Dilemma. I want to share with you how Small Experiments can be a catalyst for Innovation in any organization.

Why “Experiments”?

Some might call them “Proof of concept” (POC), yet, I favor experiment for the original meaning of the term:

“A test under controlled conditions that is made to demonstrate a known truth, examine the validity of a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy of something previously untried.”

- The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition.

The term „Experiment“ is mostly familiar in the context of scientific research. It means to set up a hypothesis, an assumption and validate whether it’s true or not. The result of an experiment is exactly that - a learning whether a question can be answered TRUE under the tested conditions.

Now, how does such certainty help me, you might ask. I very often read about the VUCA world in which it is very tough to take strategic decisions that have long-term impact due to the uncertainty it bares. Small Experiments address exactly that uncertainty by saying “Okay, what conditions or circumstances are in scope for that experiments. In other words: Which probabilities must be considered so that we have sufficient reliability and can take that decision with certainty?”

And that doesn’t only speed up business decisions but for any risky decision. We validate assumptions and hypothesis by trying them out in practice until we have enough certainty to take the decision. This is an alternative to spending countless hours in meetings just discussing the matter.

Okay, and why Small experiments?

To be clear, I’m not saying “STOP DISCUSSIONS!”. It’s about having a discussion to agree on which question, hypothesis, or assumption we must have an answer to. The more precise the question, the smaller we can draw the scope of our Experiment. A small Scope is important for multiple reasons:

Less Scope = Less Work = Less Participants

We probably all experienced discussions with larger groups of people. One comment can spark a new aspect, provoke another comment, a new aspect… and before you notice, we’re discussing a different topic.

With a defined small scope to consider, we can reduce the number of expert people that have to involved to answer the experiment’s question. Having a small team is known to have a lot of positive side effects such as a smaller number of people is easier to coordinate, builds trust faster, agrees quicker, etc. Of course, the neurodiversity of a small group can become an issue. If the participants neglect a perspective that is relevant for the context of the experiment. Yet, that’s something we can already address when building the group.

Less Scope = higher Comprehensibility

The scope of an Experiment should be small enough, that everyone in the company can immediately understand

- which question shall be answered,

- what’s the benefit for the company (and maybe for myself)

- what might be the impact when we get the answer to the question

Comprehensibility reduces anxiety

Showing potential impact of an experiment is important because you address the sorrows and concerns of employees who are afraid that change e.g. might cost their jobs. Surely that’s not the case for every single experiment, yet, being transparent about where you’re heading brings clarity and builds trust and again provides you with the chance to get feedback on concerns you’d never truly known existed in people’s minds. Comprehensibility helps to spark such thought processes in people and thus increases the chance for valuable feedback. This feedback might contain relevant variables which haven’t been on the radar of the experiment so far.

The other positive impact of accessibility and comprehensibility are also important because it shortens and simplifies the time it takes to explain the Experiment to people outside the experiment group. This is helpful e.g. when the experiment group realizes they need additional support from a person outside their group.

Summary: Advantages of Small Scope

- Definition takes less time

- Less distractions

- Less Variables = Less Cognitive-Load

- Less potential Unknowns to be considered

- Easier to comprehend

- Simpler to plan

- Less time + Less people = Costs less money

- Less Money = Less Risk

- Less Risk = easier to accept the learning that it was a step in the wrong direction

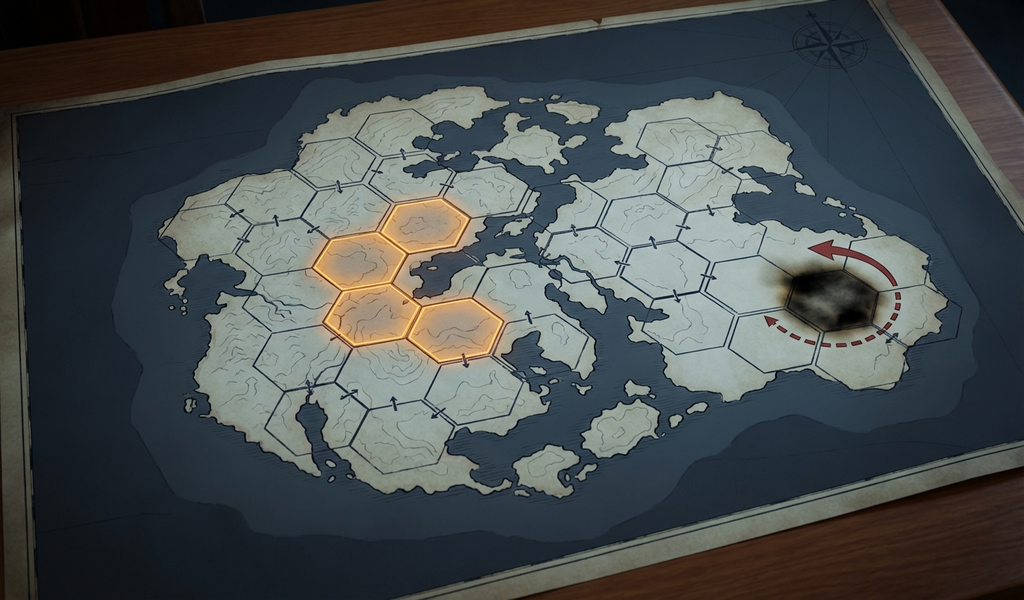

That’s why I call them Small Experiments: The risk is small, the potential benefit is high and that’s how I address what I’d call my “life’s learning” from my colleague, Stefan Tilkov. Stefan taught me to always look at the positive potential of an idea and how we could enable that instead of drowning myself in what might all go wrong. If we’re exploring an unknown path to the top of the mountain, it’s only normal we’ll find that “ah, we cannot take this way. Let’s go back and head to the left”. Small experiments support the same Management of Uncertainties for organizations that want to take yet unexplored paths to the top. Yes, we need to be able to mitigate risks and failures because this enables us to make a move at all. Fear of failure otherwise brings us to a standstill.

What next

There are different steps we could take to move towards establishing small experiments. And certainly there are still things to be looked after e.g. where the limits of scientific methods are and where methods of complexity management can support them. Thanks for taking the time to read this.

[1] https://blog.heusingfeld.de/organisation/innovation-tokens-jaxenter/

PS: I’d like to thank my colleagues who helped me reflect my thinking on the above over the course of time and finally help me put these thoughts into a series of articles: Tim Riemer, Phillipp Tepel, Jessica Paas, Phillip Ghadir, Eberhard Wolf, Julius Ganns, and Stefan Tilkov.